http://t.co/0QLiJqp via @jjiega

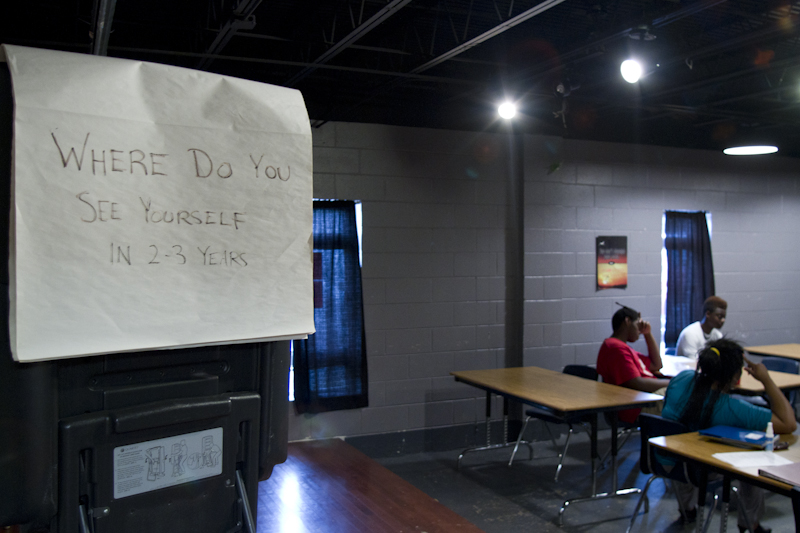

Some Clayton County, Ga., kids charged with non-violent offenses may avoid detention by attending the Evening Reporting Center weekdays from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m.

When he wasn’t skipping school or getting high smoking marijuana, he was breaking into homes with his friends just for the heck of it. He eventually got arrested and spent some days in a local detention center outside of Atlanta. After his release, a probation violation eventually landed him in a program in Clayton County, a suburban community just south of the city.

The Evening Reporting Center (ERC) is a juvenile court run alternative to incarceration program. Kids charged with non-violent offenses avoid detention center time altogether or temporarily while awaiting trial. As part of the program, buses pick them up from school and bring them directly to the ERC where they remain from 4 p.m. to about 8 p.m. weekdays. While there they receive academic assistance and life skills training. They also participate in enrichment activities and community service.

“It was either that or get locked up,” recalls Claros. “I knew this was my last chance to get it together.”

Something clicked once he enrolled in the Clayton County court program run in collaboration with the non-profit Hearts To Nourish Hope (HTNH). The ERC is operated out of a former Riverdale church building on Scott Road.

“It really changed my life,” says Claros, of the program that houses up to 10 middle and high school boys at a time from 30 days to up to six weeks. The age range is 13-17 years old. “I don’t know what opened my eyes, but I started to realize that what I was doing was not good. If I wasn’t in the program I probably would have did something else to get arrested again.”

ERC administrator Deborah Anglin says Claros’s prediction aligns perfectly with national research on juvenile crime and the reasons Clayton County Judge Steve Teske expressed to her for wanting to launch the program in 2005.

“We accept them wherever they are; everybody comes in on the same level," contends ERC chief Deborah Anglin.

Anglin, a self-described supporter of community-based prevention and alternatives to incarceration programs for at-risk young people, emphasizes that the program is also highly beneficial to its participants and their families.

“It’s safer to keep a [low-risk] kid out of detention centers,” she says. “The chances of them getting into more trouble after serving in a detention center are astronomical.”

Anglin says the ERC takes a holistic approach aiming to not only to correct the child’s behavior, but also addressing other challenges the child is facing overall.

“We teach them life skills, study skills and provide group drug counseling,” she says. “We also provide referrals for mental health and substance abuse treatment. We’re kind of like our own system of care. Our goal is to make sure that we don’t let them slip through. Our goal is to wrap our arms around them with our services.”

Anglin says ERC youth are also connected to other programs at HTNH, including employment throughout the year. There’s special emphasis on summer work experience or internship programs, she notes. HTNH also provides community-based prevention, intervention and alternatives to incarceration programs for other at-risk young people in Clayton, Fayette and Henry counties in Georgia.

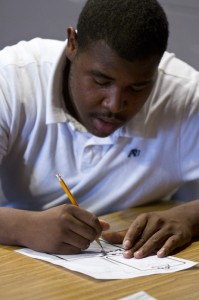

Marquan Green and his fellow ERC participants receive academic assistance and life skills training after school.

“We have many kids caught up in the gang banging scene and no adult supervision after school; the ERC takes the kids away from their gang associates and off the streets and replaces it with pro-social activities,” he says. “We have a good alternative to detention. Instead of sitting in an RYDC [Regional Youth Detention Center] they must go to school and be transported to the ERC to do more work. We have had some kids prefer to go to jail than be made to perform at the ERC.”

Data collected by the program shows it’s an overwhelming success. At times up to 95 percent of children don’t reoffend while in the program, according to Anglin.

“We serve about 60 kids a year,” she says. “We have not tracked all of them, but out of the students we have tracked six months after the program the non-recidivism rate is 93 percent. This program is based on research and best practices recognized by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.”

Judge Teske says he decided to launch the Clayton County ERC after the Casey Foundation sponsored his trip to the first one in the nation.

“The Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternative Initiative (JDAI) inspired me,” recalls Judge Teske. “They sent me to Chicago who first developed the ERC concept. They are a JDAI model court. They needed the after school programs to keep their higher risk kids from getting involved in the gang scene. It also served as an alternative to detention pending a kids hearings.”

Along with Clayton, Rockdale County, a community about twenty-four miles east of Atlanta, also operates an ERC in Georgia.

“We hope to get more by building other JDAI sites,” he says. “The Governor’s Office for Children and Families has approved funding to identify a couple more counties as JDAI sites. That work is in progress.”

ERC supporters say the program is especially successful in communities where there’s a solid commitment to juvenile crime prevention and rehabilitation.

“It helps so much that we have Judge Teske here; he understands prevention so much,” says Anglin. “In many other juvenile court systems so much time is spent trying to convince the judge that the ounce of prevention equals a pound of cure approach works. You’re not going to solve anything with these kids by just locking them.”

Claros agrees. He now maintains a steady job fixing car windshields at a nearby Clayton County shop. Later this month, he plans to enroll in the Youth Challenge Military School in Augusta in order to get a heavy dose of discipline while he earns his General Equivalency Diploma (GED). From there he hopes to enroll in college and study architecture.

“The ERC changed my life,” he says. “The staff was great. I appreciated the way they connected with me; they never judged me. If it wasn’t for this program I’d probably be locked up right now.”

Anglin says it’s always a pleasure observing the kids evolve from the “I’m-mad-I’m-here stage” upon arrival to, in many cases, eventually bonding with the staff and thriving in the program. Many end up voluntarily remaining after the required time, she says.

“Everything we do is research-based; we operate under the ‘development theory,’” she says. “We accept them wherever they are; everybody comes in on the same level. Everybody gets the same chance. We hold them accountable when they do something wrong, but they get recognition when they do something right. We set boundaries and expectations and expect them to meet them.”

Fifteen-year-old participant Eric Jerral is still early in the process. Less than a week into his obligation, he’s not sold on the program’s merits.

“It’s a waste of time; we gotta be here for four hours,” says Jerral, alternating between shifting in his chair and twisting the mass of short dreadlocks sprouting from his head. “I’d rather be at home.”

Court Liaison Edward McKenzie addresses the class as student Alan Reeves and ERC Coach Angela Green look on.

“They’re cool,” he says. “They respect you as long as you respect them.”

Fellow participant Marquan Green, 16, gives both the staff and the program high marks.’’

“I think it’s been very helpful; they’re teaching me a lot about responsibility, what you need to know to get a job and just how to think about things in a different way,” he says. “They helped me see that before I was getting in to trouble because I was following [people], not leading. Now I’m a leader. Now I see that it’s not about nobody else’s future, it’s about taking responsibility for mine.”

Green says the program’s staff has helped him to learn from the mistakes that brought him there.

“I love all of the staff,” says the aspiring barber. “[Program Director] Mr. Darryll [Starks]; that’s my homey. I think they all really care about us.”

Starks agrees that the program is making a difference.

“We’re able to plant the seeds of positivity into them and give them new tools for their tool belt,” says Taylor, who often creates activities for the young men in the program from the workbook he authored, 12 Things Every Black Boy Needs To Know. “About 40 to 45 youth enter the program each year. The court tracks many of them and 90 to 95 percent don’t reoffend. Some even go on to college, so we’re definitely making an impact.”

Edward McKenzie, who serves as the program’s juvenile court liaison, agrees.

“We expose them to different life skills – from how to write a check and open a bank account to how to fill out a job application,” he says. “Half of them don’t even know how to fill out the application so how can we expect them to find a job? Overall the program is helping them get the information that they need to be able to function as law-abiding citizens.”

Harold Johnson, a single parent from Riverdale, South of Atlanta, says he has noticed a dramatic change since his 17-year-old son, Malcolm, completed the program.

“Once he got in, I saw a 100 percent shift in his attitude; he now knows the consequences when he does something wrong,” says Johnson. “This gives them a good direction. This is a good program that saved my child’s life.”

Care and commitment may be key components of the program’s success, but operating it also takes money. It costs about $60,000 a year to execute the program and to pay its four staff members. In comparison, the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice confirms that it costs $220 a day to house a child in a detention facility; that’s close to $80,000 a year per child.

The ERC has received funding from the Casey Foundation, Clayton County and the agency now known as the (Georgia) Governor’s Office For Children and Families, along with community donations. Anglin says the price tag likely deters many other jurisdictions nationwide from creating such programs. However, she insists that reducing detention center beds saves tax dollars in the long run because it costs considerably more to incarcerate juveniles.

She insists the ERC program is an investment in a child’s future.

“We let them know that they may have been dealt a really bad hand – many of our kids have heart-wrenching life stories – but we can’t throw them a pity party,” she says. “All we can do is offer them a chance to change their life around. We let them know that it’s up to them whether or not they’re going to take this opportunity.”

Photography by Clay Duda, JJIE Staff.

Comment

© 2026 Created by Lucinda F. Boyd.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of THE STREETS DON'T LOVE YOU BACK to add comments!

Join THE STREETS DON'T LOVE YOU BACK